How Much is a Memory Worth?

Rowing is an interesting sport. It looks beautiful, smooth, and effortless.

If the public ever interacts with the sport, it’s either from watching the Summer Olympics, or it’s with beautiful pictures in magazines or financial websites.

Rowing is like a duck - what you see above the surface doesn’t tell the whole story.

Though it looks calm and relaxing, it is a sport of grit.

In October of 2009, I was on the water warming up for an important race with my teammates. We were racing against National teams, World Champions, and Universities.

Shortly after we launched, the rain turned to heavy rain, which then turned to heavy snow and near white-out conditions. (This description came from the wiki page on the storm.)

Even though we performed very well, I’m not here to tell that story.

Competing on the water in cold, wet conditions is not the most enjoyable activity I can imagine.

The first thing I think of if it’s cold, wet, and snowing outside is a fireplace and a cup of hot chocolate.

The thing is, I can recall a lot of that October race day. I vividly recall the inability to feel my freezing hands as we approached the finish line, and hoping I didn’t screw up since I did not feel in control of my oar given my numb hands.

On the other hand - the days I’ve had a warm cup of hot chocolate by a fireplace, I don’t recall any of those.

This brings me to a question I’ve thought about many times.

How much is a memory worth?

How do we value our memories? Can we value them?

We can place a dollar-value on a pontoon boat, but how do we value the memories of being out on the lake with family and friends?

The ski trip to Park City may have cost $1,500, but it was one of the best trips of my life. With the benefit of hindsight, how much would I pay for that same trip knowing how much I value the memories?

I’ve listened to people recall favorite concerts decades later with incredible detail. The ticket may have cost them $20, but the memory is hard to value. It could be 2x, 10x, or 100x in some cases.

I’m not the first one to ask these questions, as many have been researching memories for years.

Reviewing the various studies, a few things jumped out at me.

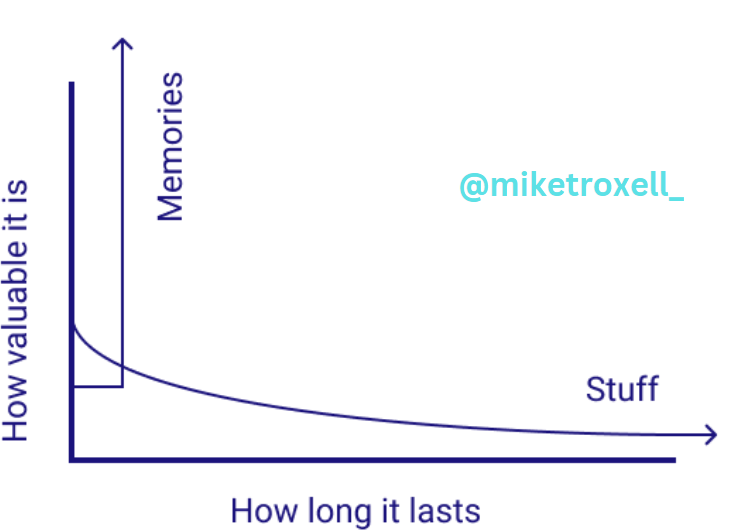

Memories of experiences tend to increase in value over time - even if the experience doesn’t last long. A concert, for example, may only last a few hours.

Physical “Stuff” tends to last longer (gadgets, jewelry, toys), but the value usually decreases over time.

You can think of experiences vs. physical goods like appreciating assets vs. depreciating assets.

Memories: Short-lived but appreciate in value.

Stuff: Long-lived but loses value.

Ironically, one piece of this equation of memories growing in value is because our ability to recall is quite poor. It’s related to the “good old days” syndrome. We think it was better back then. We think the fish we caught was bigger than it was.

“I wish there was a way to know you’re in the good old days before you’ve actually left them.”

Interestingly, as time goes on, we also tend to remember the positive things more and block out the negatives.

A study on school children had them write out the high-points and low-points of their summer vacation in two columns. Initially, each side of the ledger was about equal in length. A few months later when they re-did the exercise, the negative side was considerably shorter, while the positive got longer. At the end of the year, the bad side virtually disappeared.

Another interesting study was based on the Challenger explosion in 1986. The researchers, Ulric Neisser, then a Professor of Cognitive Psychology at Emory, and his assistant, Nicole Harsch, asked students for details about the day of the explosion. Where were you when you heard? Who were you with? What were you doing?

As a follow up to the initial questioning, the researchers asked the same questions 2.5 years later. The second time around, many of the details were different than the first. The accuracy significantly decreased, but the confidence in the answer was actually higher.

The study revealed that their memories were very clear, and very wrong.

“Nothing is more responsible for the good old days than a bad memory.”

Even negative experiences can have value

One study conducted by Dr. Thomas Gilovich, a psychology professor at Cornell University, showed that if people have an experience that they say negatively impacted their happiness, once they have the chance to talk about it, their assessment of that experience goes up.

Gilovich attributes this to the fact that something that might have been stressful or scary in the past can become a funny story to tell at a party or be looked back on as an invaluable character-building experience.

It completely makes sense - how often have we heard the following? “Looking back, the (failure) was the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Sara Blakely, billionaire founder of Spanx, stated something along the lines of - “If I had aced the LSAT exam to get into law school, there would be no Spanx and I’d be a lawyer.”

Ryan Leaf, former NFL 1st Round Draft pick, and arguably the biggest “bust” in NFL history said A 32-month prison sentence saved his life. Prior to going to prison, he developed a painkiller addiction, committed burglary, and attempted suicide.

We all have negative experiences - job loss, breakups, financial hardships, other difficult times. For the challenges that I have experienced, climbing the metaphorical mountain wasn’t fun at all, but it looks a lot better in the rearview mirror.

Experiences are Shared. Things are Compared.

This was one of my favorite discoveries in researching this topic. If you and I experience the same thing, that creates a bond. It doesn’t matter if we hiked Half-Dome together, or if we hiked it in different decades. We will still bond over it and discuss it as if we conquered it together.

On the other hand, when it comes to “stuff,” we don’t share, we compare. If we both drive a nice car, we’re interested in the stats. The exact model. The year. The engine. The price negotiated. The gas mileage. The sun roof. It doesn’t matter that we both have a sweet TV, I want to know how many pixels and inches.

How do we know when we’re creating memories?

Dan Ariely, a behavioral economist, and Duke University professor, recommends some variety and doing something to make the memory more intense.

One example of variety is to add in an adventure, such as kite-boarding lessons, during your relaxing beach getaway sipping Mai Tais. Ariely suggests that a week of Mai Tais may be nice, but the lack of variety and intensity means the days will all blend together.

For intensity, a personal example is a trip to Banff National Park. I recall seeing several stunningly blue glacier lakes, but the one I remember most vividly is Lake Louise. Why? Because I jumped in.

It was quite painful at the moment of entry - the ice-cold water and the sharp rocks at my feet. Though I’ll never forget the feeling of euphoria afterwards, especially when I had hot chocolate in hand. Likely the only hot chocolate that is seared in my mind.

The memory is so vivid, that I recall meeting an amateur photographer named Terry. He was on a trip for photography lessons. After the trip we exchanged photos via email - he snapped some of us tiptoeing into the water, and we snapped some of him trying to catch the perfect shot as the sun was setting over the Canadian Rockies.

In the book, Adventures in Memory, the sisters Hilde and Ylva Østby describe memory networks being built and impacting the strength of understanding/remembering an event. Their takeaway is that our memory is tied to our familiarity and interest. If you enjoy cooking, you’re much more likely to remember the sushi class. If you like skiing, you’ll never forget Heli-skiing in Japan.

The takeaway: If we want to consciously create a lasting memory, choose a unique (variety), exciting (intense) event that you already have an understanding or interest in.

Money for Memories

Knowing that money allocated in the proper way can create memories, would that change how we spend money? What if I didn’t buy this or that? What if I lived in a cheaper home with a longer commute? I could have gone on more ski trips; I could have created more memories. But the longer commute may come at the expense of memories in the living room with the ones I love the most.

It works both ways, allocating money for memories means it becomes hard to turn off the spigot.

Spending $1,500 on a single ski trip is one thing, but the FOMO factor means I’ll never want to miss another one for the rest of my life.

It’s similar to life-style creep or Hedonic Adaptation. I don’t know many people that go from a Mercedes to a Kia. Once you ski a season on endless fresh powder, it’s tough to go back to icy conditions on the East Coast. No one wants to go from eating fresh oranges off the tree to an old hotel fruit salad where only the honeydews remain.

How much would you give up for memories?

A high paying job at the cost of not seeing your family. How much money would it take for you to not see your family for the next 12 months? For some there is a price, for others there isn’t. Similar to the long commute - what form does the price of the commute come in? Am I paying in minutes or memories?

After reading this, “memory creation” may be one additional nudge for some to swipe their credit card, as if we needed another reason :) Although, money is a tool and part of my job is to figure out how best to allocate resource - sometimes it is stocks and bonds, other times it is surf lessons or concert tickets.

I am curious to learn about some of your experiences spending money: What memories are valuable to you? What “things” that you purchased and were excited about five years ago, no longer do the trick?